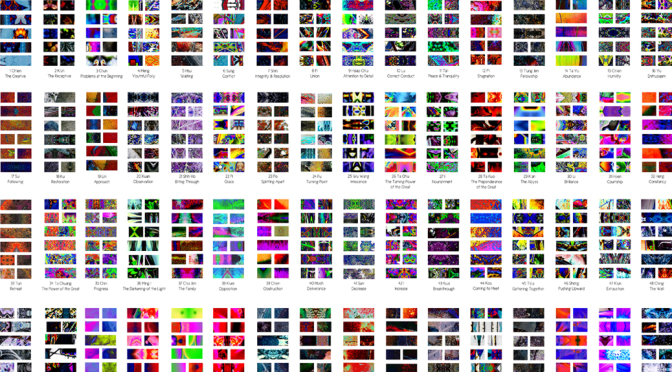

The I Ching, which we can well call the experimental foundation of classical Chinese philosophy, is one of the oldest known methods for grasping a situation as a whole and thus placing the details against a cosmic background.

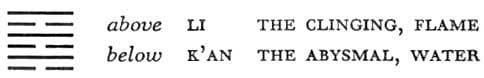

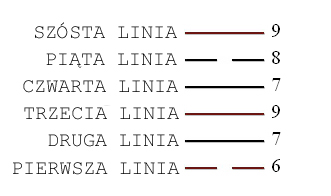

Unlike the Greek-trained Western mind, the Chinese mind does not aim at grasping details for their own sake, but at a view which sees the detail as part of a whole. For obvious reasons, a cognitive operation of this kind is impossible to the unaided intellect. Judgment must therefore rely much more on the irrational functions of consciousness, that is on sensation (the “sens du réel”) and intuition (perception by means of subliminal contents). The I Ching, which we can well call the experimental foundation of classical Chinese philosophy, is one of the oldest known methods for grasping a situation as a whole and thus placing the details against a cosmic background—the interplay of Yin and Yang.

864

This grasping of the whole is obviously the aim of science as well, but it is a goal that necessarily lies very far off because science, whenever possible, proceeds experimentally and in all cases statistically. Experiment, however, consists in asking a definite question which excludes as far as possible anything disturbing and irrelevant. It makes conditions, imposes them on Nature, and in this way forces her to give an answer to a question devised by man. She is prevented from answering out of the fullness of her possibilities since these possibilities are restricted as far as practicable. For this purpose there is created in the laboratory a situation which is artificially restricted to the question and which compels Nature to give an unequivocal answer. The workings of Nature in her unrestricted wholeness are completely excluded. If we want to know what these workings are, we need a method of inquiry which imposes the fewest possible conditions, or if possible no conditions at all, and then leaves Nature to answer out of her fullness.

Czytaj dalej