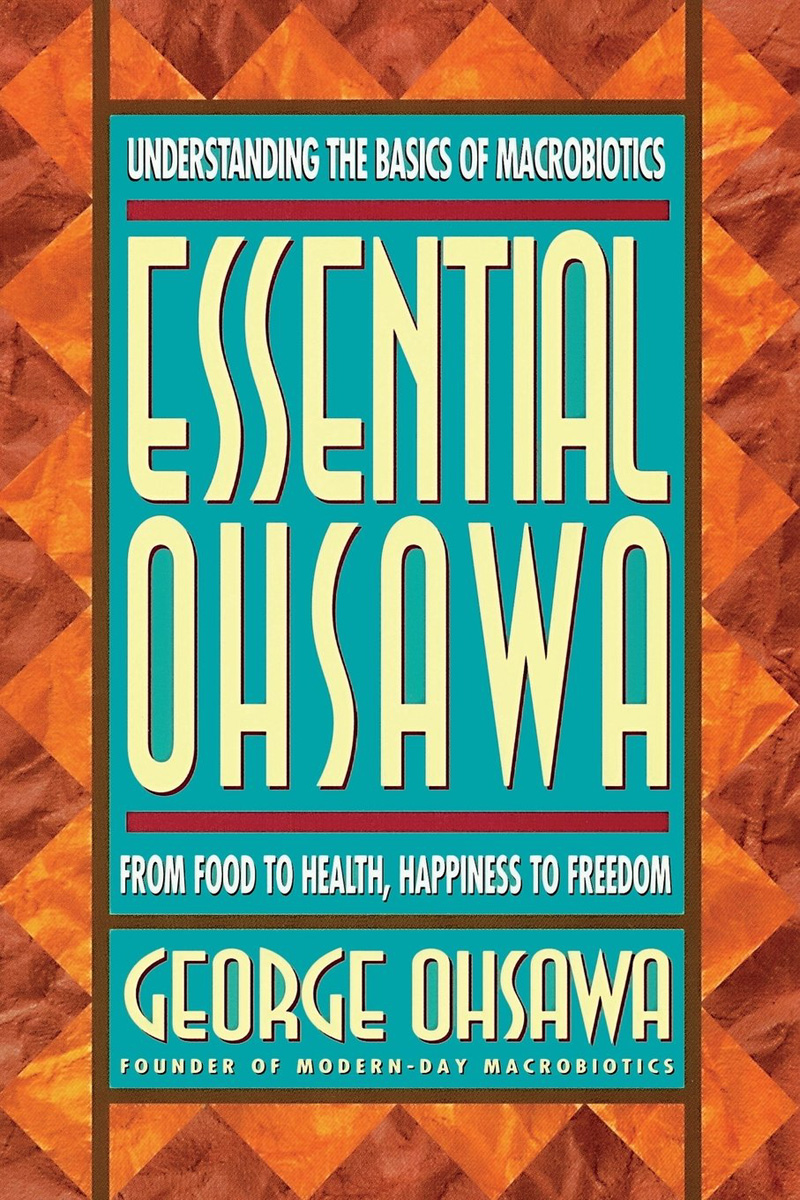

Culinary art is life’s art. Our health and consequently our happiness, our liberty, and even our judging ability are under the influence of this art. This is why only the best disciples are selected as cooks in the great schools or Buddhist convents. If you are not a good cook, you simply have to learn the culinary art.

Culinary preparation is, indeed, fundamental in enabling man to attain self-realization through Far Eastern medicine.

To eat is to create a new life for tomorrow through the sacrifice of the vegetal realm and its products. If mistakes are made, this is, literally, the “original sin.” This is symbolized in the myth of the Garden of Eden.

- Eat whole grains and local, seasonal vegetables, using a bit of salt, oil, and traditional condiments.

- Chew each mouthful of food fifty times or more.

- Drink only what is necessary.

- Work hard physically.

True health is that which you yourself have created out of illness. Only if you have produced your own health can you know how wonderful it actually is. For this reason, many healthy people squander away their health; through ignorance, they spoil it without knowing its true value. He who knows the real worth of health spreads his joyous knowledge by telling others what he knows. If you are healthy but do not try to give to others of the happiness it brings, you are unaware that happiness is priceless.

True health can be established only by conquest over bad factors that are menacing your life, without using any violence; rather, by a good cooperative and complementary agreement, a universal solidarity, or a most intimate brotherhood established with all the evildoing factors. The fundamental ideas of symptomatic medicine, which tries only to destroy noxious factors, are childish, primitive, unmanageable, exclusive…

Sickness and weakness are necessary in this world. It is through our efforts to change them into health that we learn gratitude.

It is disease that leads us toward health. If one errs in the use of therapeutics, for instance by following symptomatic medicine, this is the starting point for the principles of health. This is the Order of the Universe.

Illness is the very helpful guide that leads us toward an understanding of the constitution of the universe.

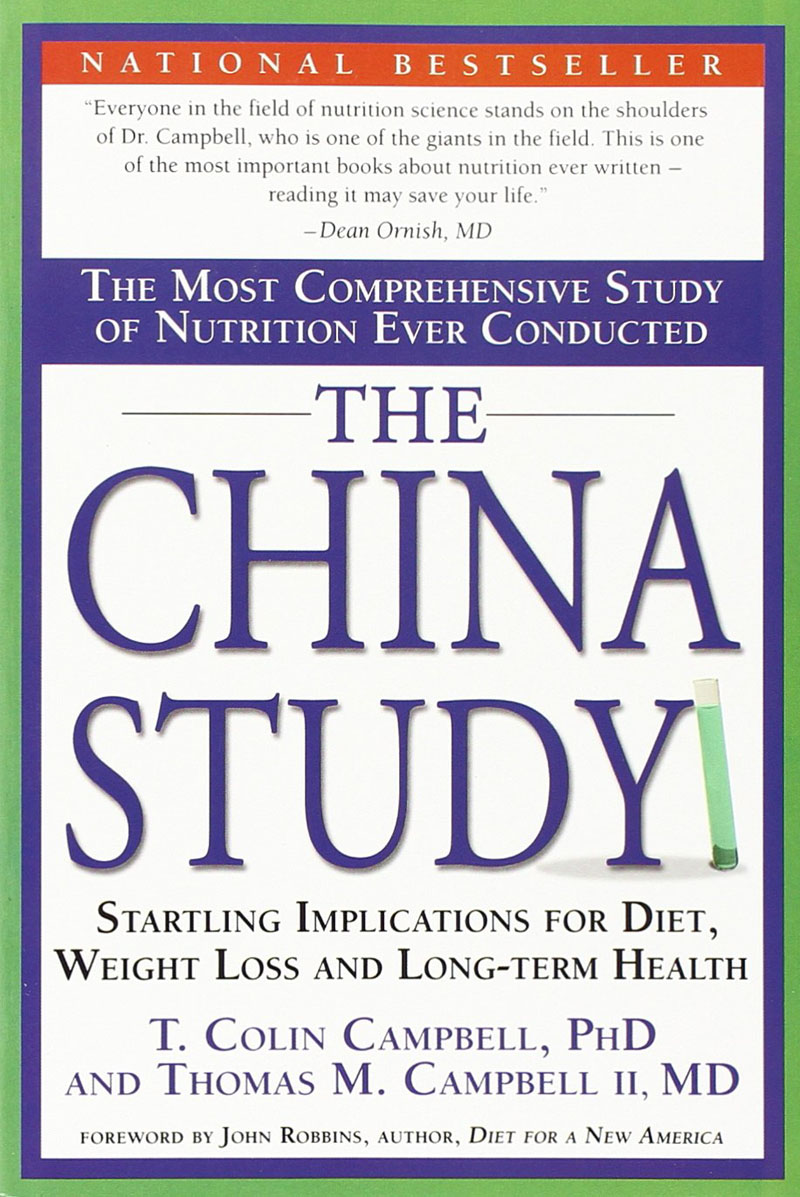

As man nourishes with foods, he should carefully develop his spirit. All great or happy people have absorbed much more food of the spirit than physical foods. Books are of this invisible nourishment. As one can find foods of various qualities, from the best to the worst, likewise there exist all sorts of spiritual nourishment. […] Therefore, if you have the intention of reading a good book, you should buy what was published at least twenty years ago. Books at least two hundred years old that one appreciates are certainly good. The book whose value has been recognized for two thousand years is the true best seller.

If we are unhappy, we are violating the Order of the Universe.

Accept everything with greatest pleasure and thanks. Accept misfortune like happiness, disease like health, war like peace, foe like friend, death like life, poverty like prosperity— and in case you do not like it or you cannot stand it, refer to your universal compass, the Unifying Principle; there you will find the best direction. Everything that happens to you is what you are lacking. All that is antagonistic and unbearable is complementary. He who can embrace his antagonists is the happiest man.

Without a basic principle to follow, any sort of practice is no more than superstition. The principle (spirit) of macrobiotic living lies in recognizing, experiencing, and understanding nature. This is Tao—the return to and contemplation of God.

Any theory, be it scientific, religious, or philosophical, is quite useless if it is too difficult to understand or impractical for daily living.

Continue reading →