The awakening of the spirit is accomplished because the heart has first died. When a man can let his heart die, then the primal spirit wakes to life. To kill the heart does not mean to let it dry and wither away, but it means that it has become undivided and gathered into one.

Master Lü-tsu said, The decision must be carried out with a collected heart, and not seeking success; success will then come of itself. In the first period of release there are chiefly two mistakes: indolence and distraction. But that can be remedied…

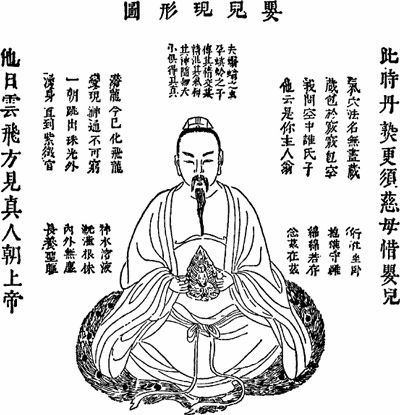

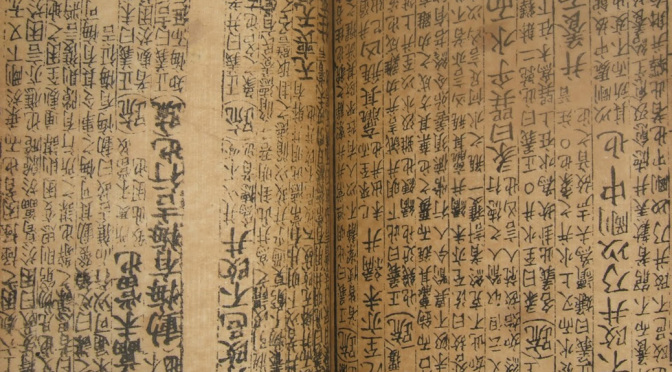

Meditation, Stage 2: Origin of a new being in the place of power

The two mistakes of indolence and distraction must be combated by quiet work that is carried on daily without interruption; then success will certainly be achieved. If one is not seated in meditation, one will often be distracted without noticing it. To become conscious of the distraction is the mechanism by which to do away with distraction. Indolence of which a man is conscious, and indolence of which he is unconscious, are a thousand miles apart. Unconscious indolence is real indolence; conscious indolence is not complete indolence, because there is still some clarity in it. Distraction comes from letting the mind wander about; indolence comes from the mind’s not yet being pure. Distraction is much easier to correct than indolence. It is as in sickness: if one feels pains and irritations, one can help them with remedies, but indolence is like a disease that is attended by lack of realization. Distraction can be counteracted, confusion can be straightened out, but indolence and lethargy are heavy and dark. Distraction and confusion at least have a place, but in indolence and lethargy the anima alone is active. In distraction the animus is still present, but in indolence pure darkness rules. If one becomes sleepy during meditation, that is an effect of indolence. Only breathing serves to overcome indolence. Although the breath that flows in and out through the nose is not the true breath, the flowing in and out of the true breath takes place in connection with it.

The Secret of the Golden Flower