The vision of light, is an experience common to many mystics, and one that is undoubtedly of the greatest significance, because in all times and places it appears as the unconditional thing, which unites in itself the greatest energy and the profoundest meaning. Hildegarde of Bingen, an outstanding personality quite apart from her mysticism, expresses herself about her central vision in a similar way. ‘Since my childhood,’ she says, ‘I have always seen a light in my soul, but not with the outer eyes, nor through the thoughts of my heart; neither do the five outer senses take part in this vision. The light I perceive is not of a local kind,but is much brighter than the cloud which bears the sun. I cannot distinguish height, breadth, or length in it… What I see or learn in such a vision stays long in my memory. I see, hear, and know in the same moment. … I cannot recognize any sort of form in this light, although I sometimes see in it another light that is known to me as the living light… While I am enjoying the spectacle of this light, all sadness and sorrow vanish from my memory…’

I know a few individuals who are familiar with this phenomenon from personal experience. As far as I have been able to understand it, the phenomenon seems to have to do with an acute state of consciousness, as intensive as it is abstract, a ‘detached’ consciousness, which, as Hildegarde pertinently remarks, brings up to consciousness regions of psychic events ordinarily covered with darkness. The fact that the general bodily sensations disappear during such an experience suggests that their specific energy has been withdrawn from them, and apparently gone towards heightening the clarity of consciousness. As a rule, the phenomenon is spontaneous, coming and going on its own initiative. Its effect is astonishing in that it almost always brings about a solution of psychic complications, and thereby frees the inner personality from emotional and intellectual entanglements, creating thus a unity of being which is universally felt as ‘liberation’.

C. G. Jung, Commentary to “The Secret of the Golden Flower”

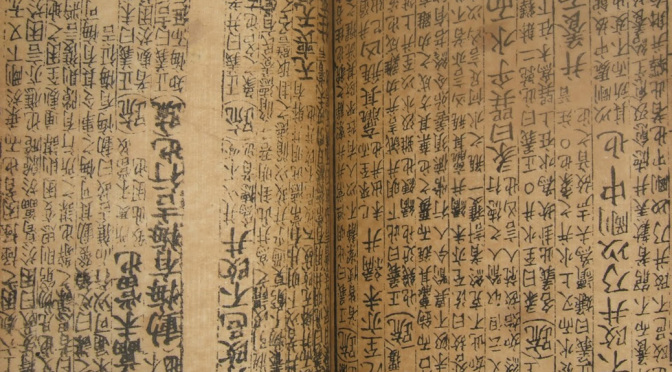

Hildegard's mandalas